Printmaking is an exciting genre that is enjoying a revival with new print shops emerging in communities across the Northwest Territories (NWT). The Sambaa K’e Studio in Trout Lake holds exhibitions and workshops, employing a variety of exciting and unique printmaking techniques including Gyotuku, the art of Japanese fish printing. In the capital city of Yellowknife, individual printmakers are creating exceptional works from their home studios where they play with contemporary lines and techniques.

James Houston first introduced printmaking in the eastern arctic in the small community of Cape Dorset in 1957. Using the principles of Japanese woodcut printing, he adapted the techniques to work on stone, a material readily available. This technique quickly spread to other communities in the Arctic. The use of stone in this way was exclusive to Canada’s North. Inuit embraced this contemporary form of art as a means to express their stories and culture, and the art market responded with great enthusiasm.

When the first Inuit prints appeared in southern markets in 1959, Canadian and international art buyers were entranced. The rich variety of imagery – from the narrative, to the illustrative, to the purely imaginary – reflected Inuit life both past and present. The prints explored spatial relevance in a whole new way; there were obvious themes of shamanism, as well as depictions of northern wildlife. These themes were exotic and intriguing to North American and European audiences.

Holman Eskimo Co-operative, NWT

In the remote community of Holman (now called Ulukhaktok), Father Henri Tardy, OMI, was looking for a project that would bring economic benefits to his Inuvialuit parishioners. He helped establish the Holman Eskimo Co-operative in 1961 and encouraged prospective artists to begin creating art there. In 2008, the Business Development Incentive Corporation (BDIC) established and began operating the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre.

At first, the Holman artists experimented with sealskin stencils, shaved with Father Tardy’s own razor. The first 10 stencil prints were sent to the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council for review in 1963. In 1964, Northern Affairs sent Barry Coomber to Holman to teach stone-cut techniques – the print style popularized by Houston-trained printmakers in 1957. Stone was readily available in Holman and far more practical than sealskin.

In 1965, Helen Kalvak, Victor Ekootak, Jimmy Memorana, Harry Egotak and William Kagyut created the first annual Holman Print Collection of 30 limited edition prints, which became an immediate market and artistic success. Over the years, different printmaking techniques have been used in the annual Holman Eskimo Co-operative collections.

Between 1965 and 1976, stone-cut was the exclusive method. Early prints featured strong shapes and single bold monochrome colours such as red, blue, black or brown. Print Shop Manager, John Rose, introduced lithography in 1977 and stencil printing in 1980. Wood-cuts were tried in the 1980s, but proved impractical. Since 1986, print collections have included both stencils and lithography.

In 2001, the Winnipeg Art Gallery staged “Holman: Forty Years of Graphic Art”, an exhibition that recognized a truly remarkable collection of artists and their work. A virtual exhibit resulting from that show can be viewed at www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/Holman

While the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre has not produced an Annual Print Collection since 2000, individual artists continue to make and sell prints today. The artists of the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre hope to create an annual print collection to release to the world in the near future.

How Prints are Made

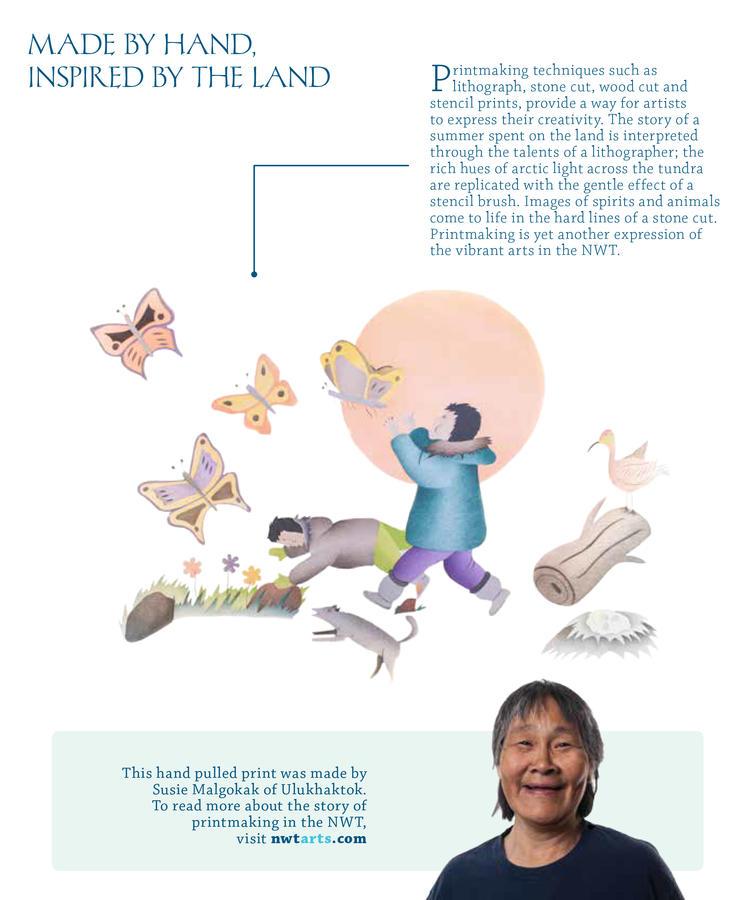

Printmaking is a collaborative process. Artist, printmaker and arts advisor work together to create, select and produce prints. Prints are created by hand, from preparing materials, to applying colour, to individually signing each print.

On the signature line, the first name is the name of the artist, followed by the printmaker’s name. If the artist and printmaker are the same person, only one name appears. Authentic prints from Ulukhaktok feature an ulu mark on the bottom corner, an idea picked up from Japanese artists’ chop marks.

Finished prints are numbered to indicate the size of the edition, which is never more than 50. After the edition is “pulled” from the plate, stone or stencils, the printing surface is defaced to prevent more prints from being made, thus “limiting” the edition. The original drawings often become valuable collector’s items.

Stone-cut Prints

Smooth limestone, quarried near Minto Inlet, is used for stone-cut prints. A reverse image of the selected drawing is traced onto the stone. All the stone surrounding the image is removed, leaving a series of raised areas representing the image on the face of the stone. These raised surfaces are inked and a thin sheet of paper is placed over the inked surface. The paper is pressed gently and firmly against the stone by hand with a small padded disc. The paper is then “pulled” from the surface and hung to dry. For each new print, the surface of the stone is inked anew.

Lithography

Lithographs are created using a flat plate, oil and water. The artist creates the image directly on the smooth plate using an oil-based crayon. A separate plate is created for each colour. A film of water is applied to the plate and then a layer of greasy ink. The water is repelled by the crayon image, but the ink adheres to the oil-based crayon. Paper is laid on the stone or metal plate and a press transfers the colours to create the finished image. It is important that each plate match precisely with the previous one, to create the multi-coloured image.

For more information, download the brochure.